Forecast’s asymmetrical structure spreads across the landscape at the same time as it radiates upwards; the artwork looks both internally to its various connecting components and externally to its surroundings. Limb-like and jointed elements point to Henry’s sustained interest in where and how pieces come together. Here, each piece of the sculpture suddenly slims as it approaches a joint. At these joints, Forecast’s leg-like supports become elbows or knees and create a secondary quasi-plinth that supports the upward-reaching vertical components. Construction greatly appealed to Henry, particularly the practicality of joints. He has said about his early art that “the nuances of construction, in joining, sometimes played a larger role than the forms themselves.”[i] Henry’s attention to connections, both internal and external, includes an artwork’s interaction with its surroundings. Forecast’s horizontal thrust speaks to its surrounding structures: Court Theater, the David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, and the Cochrane-Woods Art Center. These buildings, noted for their pronounced horizontality that echoes the Midwestern prairie style, complement the sculpture’s outward-reaching legs.

Forecast, as well as Henry’s larger body of work, intensely focuses on the practicality and physicality of construction. He enjoys the physicality involved in cutting steel and welding, as well as “the most exciting stage of building” when “sections are finally lifted into place and [he] is confronted with the reality of the scale, the physical appearance, the actual balance, weight and structural grounding.”[ii] Even at the smallest scale, Henry’s sculptures make no attempt to hide the reality of their construction. Where each beam meets and bends, the pieces are held together with visible bolts, which have become part of the sculpture. The pieces meet imperfectly, never completely coming together. Instead, they create gaps and in-between space within the object’s joints. In this way, Henry makes construction visible to the viewer, here and in larger sculptures. For example, Bridgeport, installed in the foyer of Chicago’s Thompson Center, is built similarly to Forecast in that it has the same visible bolts.

Henry conceptualizes an individual artwork in relation to his prior oeuvre: “Each sculpture is part of a continuous sentence, all referencing one another and each an integral part of a greater whole. … it is very much about the process of working together to extend the influence of a particular part of a visual vocabulary.”[iii] Sculptor Stephen Luecking relays that Henry has come to think of “his entire body of work as a symphony of which the individual sculptures comprise the passages.”[iv] The individual artworks also echo the idea that a whole is greater than the sum of its parts: composed of simple geometry—a straight line, a 90-degree surface, an obtuse angle—the final artwork becomes something more. Henry says, “when the pieces are put together, assembled, something quite different happens. This very rigid kind of architecture becomes organic. … There are big sweeps. All kinds of things start to happen. The sculptures seem to move.”[v]

Henry has also conceptualized his sculptures as “drawings in space,” which respond to not only their surrounding environments but to their anticipated human viewer as well. Henry’s larger artworks, such as Illinois Landscape no. 5, invite the viewer to walk in and around their supporting legs. Viewers can experience the object not just in the round but also from below. In this way, Henry carefully considers each artwork’s scale. Although much of his well-known public art—including Illinois Landscape no. 5, installed at Governors State University—was conceived for a particular context, Henry is wary of the lure of site-specificity. In his experience with large-scale sculptures, few artworks remain in the same position or context they were originally made for. Instead, the artist seeks to create “really strong, compelling individual statements that can hold their own wherever you put them.”[vi]

Henry believes that an artwork’s relationship to its surroundings is one of the key challenges of modern sculpture. Through his sculptures, the artist both consciously and intuitively responds to this problem. His forms build on and respond to sources in the observable world—buildings, landscapes, and viewers. Henry lived and worked in Illinois for nearly two decades, observing his surroundings closely; his public sculptures here respond to the state’s flat, low horizon and the wide unobstructed spaces of its prairies. Illinois provides a landscape to hold his “drawings in space.” Ultimately, Forecast is part of Henry’s Illinois legacy; it speaks to Henry’s body of work in and around Chicago. Like Henry’s other local public art, Forecast shows how “sculpture adds to the monumental image of Chicago.”[vii]

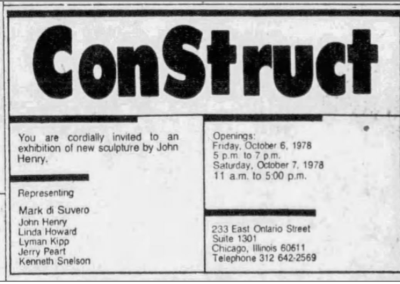

Starting in the mid-twentieth century, sculptures by internationally-renowned artists were installed all over this city: “the Picasso” in Daley Plaza, Isamu Noguchi’s fountain behind the Art Institute, Alexander Calder’s Flamingo in Federal Plaza, and Claes Oldenburg’s Batcolumn in front of the Harold Washington Social Security Center in the West Loop. At the same time, Chicago-based sculptors like Henry rose in renown and popularity. Henry, Richard Hunt, Egon Welner, and Abbott Pattison influenced the evolution of sculpture across the city with both temporary exhibitions and permanent installations. Henry was notably part of the 1968 Eight American Sculptors exhibition in Pioneer Court (then called Equitable Plaza). A student at the time, Henry recalled the significance of Eight American Sculptors: “This may have been the first such exhibit anywhere. Before this, exhibits usually held artworks large enough to be shown outdoors, but not specifically built to be shown there.”[viii] Luecking describes how prior to this exhibition, there existed no tradition of placing Modernist sculpture into a public place, with one exception: a year earlier, Chicago Mayor Richard Daley had unveiled the iconic Picasso. Henry also co-founded the artist group ConStruct, which counted Lyman Kipp among its six founding members. ConStruct’s artists aimed to take total control over the way their art was exhibited and presented, and to advocate for both themselves and for large-scale sculpture. One of Chicago’s “most unusual” artist-run spaces—as well as Henry’s last major enterprise in Chicago—ConStruct successfully ran for ten years from an upper floor of a high-rise overlooking the MCA.[ix]

Although Henry left Chicago in the 1980s, his art around the city stands as a testament to his place in Chicago’s history of modern sculpture. Arris, a monochromatic yellow sculpture which spreads laterally across its site, stands on Chicago’s John Henry Way (Cermak Ave. at the intersection with Calumet Ave.). Bridgeport dominates the central courtyard of the James R. Thompson Center (formerly the State of Illinois Center). Shortly after its installation, Illinois Landscape No. 5 at Governors State University made headlines as one of Chicago’s “sculpted treasures.”[x] While Illinois Landscape No. 5 is one of Henry’s largest public sculptures, Forecast is almost unassuming. Only slightly taller than a standing person, the structure sits in the Court Theater’s quiet courtyard, tucked away from most pedestrians’ sightlines. However, it equally exemplifies Henry’s sculptural vocabulary and, despite its small size, feels just as monumental. Grounded and stable, clear and structured, the work holds its own. Like the city it inhabits, the sculpture rises out of the endlessly flat Illinois landscape.

[i] Finn, “John Henry Talks with David Finn,” 36.

[ii] Finn, “John Henry Talks with David Finn,” 36.

[iii] John Henry, “Artist Statement,” in Drawing in Space: The Peninsula Project (David McDonald, 2008), 21.

[iv] Stephen Luecking, “Lines of Giants: The Sculpture of John Henry,” in John Henry (New York: Ruder Finn Press, 2010), 29.

[v] Victor Cassidy, “Sculpture as a Symphony: A Conversation with John Henry,” Sculpture 27, no. 10 (December, 2008), 52-53.

[vi] Finn, “John Henry Talks with David Finn,” 38.

[vii] Marion E. Kabaker, “Sculpture Adds to the Monumental Image of Chicago,” Chicago Tribune, August 25, 1978, 27.

[viii] Luecking, “Lines of Giants: The Sculpture of John Henry,” 19.

[ix] Luecking, “Lines of Giants: The Sculpture of John Henry,” 22.

[x] Marion E. Kabaker, “Sculpture adds to the monumental image of Chicago,” Friday, August 25, 1978, 27 – 29.

Written by Claire Rich