Chinese Stone Lions at the Cochrane-Woods Art Center

Unknown artists

North pair:

Chinese, c. 16–17th century

Marble with concrete base

North East: 23 x 36 x 52 in. (without base)

North West: 22 x 39x 50 in. (without base)

Located outside of the north entrance of the Cochrane-Woods Art Center, 5540 S. Greenwood Avenue

Gift to the Department of Art History from the Art Institute of Chicago from a bequest of Edith Farnsworth

South pair:

Chinese, early 20th century

Marble

South East: 15.5 x 35 x 48 in.

South West: 14.5 x 32 x 46 in.

Located outside of the south entrance of the Cochrane-Woods Art Center, 5540 S. Greenwood Avenue

Gift to the Department of Art History from the Art Institute of Chicago from a bequest of Harley Farnsworth MacNair and Florence Wheelock Ayscough MacNair

Two pairs of Chinese carved stone lions of the type popularly known as “foo dogs” stand guard outside the entrance to the Cochrane-Woods Art Center on the north side of campus, one pair placed at the north entrance and the other facing south into the courtyard shared with the Smart Museum of Art. Pairs of guardian lions have a long history in China. They began to appear frequently in the early medieval period introduced with Buddhist imagery from southern and central Asia, the lions signifying the nobility of the Buddha and his power in the spiritual world. As lions are not native to China, Chinese envisioned them as fantastic, supernatural creatures and fierce protectors against malevolent forces. From as early the seventh century they are depicted as massively broad-chested with thick curling manes. Frequently shown much larger than life-sized, they were included among the pairs of stone animals lining the spirit roads approaching royal tombs. Lions sculptures also served as guardians for temples and palaces. In the late imperial period, the Ming and Qing dynasties, they appear as a male and female pair, both shown with manes and mouths open in a roar. A monumental pair believed to be from the Ming period in “Forbidden City” palace in Beijing, each has one front paw raised, the female gently and rather playfully rests her paw on a small lion cub, and the male has an embroidered ball like one made for a pet. When these were noted by Western travelers and collectors in the nineteenth century, they were mistakenly called dogs.

Archival Materials

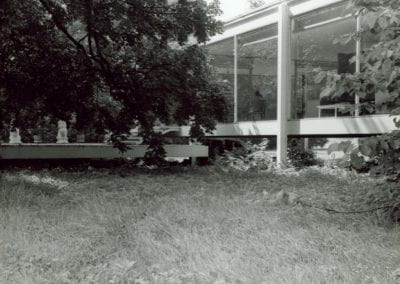

Lions outside of the Farnsworth House, Plano, IL, undated

Courtesy of the Newberry Library, Midwest MS Farnsworth, Bx.1 Fl.13, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe house

Lions outside of the Farnsworth House, Plano, IL, undated

Courtesy of the Newberry Library, Midwest MS Farnsworth, Bx.1 Fl.13, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe house

Photo of MacNair home on Woodlawn Avenue, 1937

Courtesy of Florence Ayscough / Harley MacNair Collection, Armacost Library Special Collections, University of Redlands

Gallery

Click on the image to zoom in

Lions outside of the Farnsworth House, Plano, IL, undated. Courtesy of the Farnsworth House. (2 of 5)

Lions outside of the Farnsworth House, Plano, IL, undated. Courtesy of the Newberry Library, Midwest MS Farnsworth, Bx.1 Fl.13, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe house. (3 of 5)

Lions outside of the Farnsworth House, Plano, IL, undated. Courtesy of the Newberry Library, Midwest MS Farnsworth, Bx.1 Fl.13, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe house. (4 of 5)